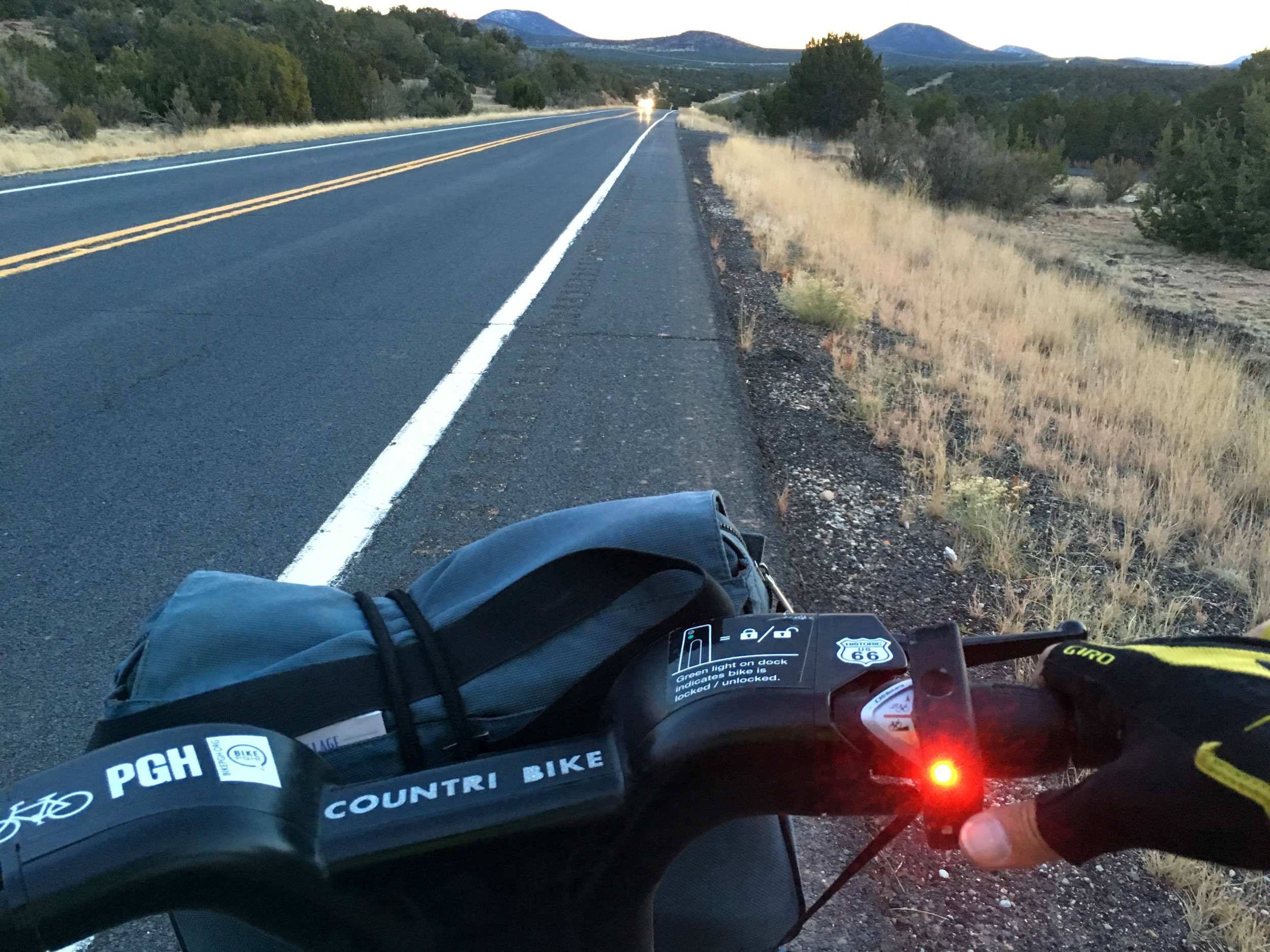

That red light is not good.

I’m late, but need to see her one last time. I walk to the edge and stare into this magnificent chasm. The clouded sky mutes the colors, but even on a dreary day my eyes can’t process how big and bold this canyon is — an apt metaphor for a Citi Bike crossing a continent.

It’s 60 miles from the South Rim to my destination, the town of Williams on Route 66. I pedal away from the canyon through Ponderosa pines along the forested Arizona Trail.

The trail leads to Tusayan where a cluster of hotels offers budget travelers Grand Canyon access just beyond the park’s limit. Outside a grocery store I assemble ShareRoller for the first time. This lithium battery-powered motor is my new weapon to fight endless desert, fierce headwinds and long inclines. I didn’t buy it; the founder asked me to test drive his invention.

ShareRoller is a 3D-printed box housing two high-powered lithium batteries. A motorized wheel pops out like an arm to press against the bike’s front tire and move it fast and smooth like the breeze. Or so I imagine.

I immediately regret not testing this in advance. The piston that locks the unit in place won’t catch the anchor hole on the bike, which is normally used to lock the bike into a docking station.

I push, I pull, I scream, I swear. The piston won’t catch. My fingertips bleed from trying so hard. I troubleshoot for an hour on the phone with ShareRoller’s founder. Eventually I’m able to MacGyver the battery box in place with rubber gear ties.

It’s almost noon and I’ve got 52 miles to go. I’m not worried. With a battery-powered motor, in theory I should be able to cruise at 15 mph. In practice, not so much.

Lest you think a motor is cheating, let me look you in the eye and say that my journey just got harder. The motor and battery charger weigh a whopping 10 pounds. Cross-country cyclists obsess about shaving ounces off their load. I just added two bricks to my bag. When the unit is stored in my trailer, the drag is for real.

Moreover, even when mounted to the bike, the motor adds rolling resistance against the front tire. This is not a sit-back-and-relax kind of thing. Biking now requires even more effort, kind of like riding through mud. The benefit comes when I engage the throttle and the motor peps to life. I’m pedaling just as hard as before, but the motor magnifies my output.

I’m going faster. Sometimes. The battery assist isn’t strong enough to motor me up hills. It’s only useful on straightaways and actually slows my roll downhill.

The road south to Williams is a barren stretch I'd like to fast-forward. Despite only intermittent usage, the battery is draining fast. A combination of headwinds, rolling hills and the weight of the trailer are to blame.

At a junction in Valle, I stop at a gift shop not for last chance Grand Canyon tchotchkes, but to recharge the battery at an outdoor electrical outlet while giving a phone interview to Bicycle Times magazine (online version is here).

Forty minutes later I hang up and have a choice to make: keep charging or keep biking. It’s almost three o’clock and I’m 29 miles north of Williams with about two hours of daylight remaining. Fifteen miles per hour with the motor and I’ll make it just in time, right?

Wrong. Headwinds ramp up in ferocity and the battery charge goes into free fall. Worse, I become addicted to the throttle. I know it’s draining the battery, but it’s helping me cut through these headwinds. Without the throttle it’s like pedaling through molasses. So I press the throttle again. And again. I know it’s bad, but can’t stop… like the struggle to decide which chip is your last before closing the bag.

I pull over to check my progress. Twenty-two miles to go. My voice cries out in the wilderness. I’ve gone only seven miles in 75 minutes with motorized assist. It’s now 5:12 PM and I have six minutes until the sun officially sets.

If I weren’t on a bicycle in the middle of f’ing nowhere, I’d cherish the soft yellow, pink and purple streaking across the pastel sky. I beg the sun to stay for another hour or so, “drinks on me” kinda thing.

I strap on a headlamp and clip a red tail light to my seat pole to prepare for the curse of darkness. I’m alone and scared. Along the C&O Canal in Maryland I biked once until darkness stopped me right at a campground along the trail. In Tucumcari, New Mexico I arrived at a fabulous motel just as darkness fell. Never have I been so far from a destination at dusk. The motor is now useless when I need it most, sputtering like the last drops of soda sucked through a straw.

I’m not me anymore. I’m a stranger in survival mode, too shocked for self-pity. Twenty mph winds blast me. My defense is down. Cinderella technology has turned into a 10-pound pumpkin.

Arizona 64 is a two-lane road, fortunately well-paved with a rumble strip on the decent shoulder. However, rush hour traffic, at least for rural Arizona, is cause for concern. Tour buses blow by me with no clearance. I curse and snarl at the reclining passengers nodding off in warmth on their expedited way back to somewhere safe.

In the last dusting of daylight I'm hit with a gut punch of horror. A severed head. That's how I react when I realize my flashing red tail light is dead. I’m riding in total darkness without a light. I scavenge reflective lane markers torn from the pavement and affix them to the trailer.

To be sure, I’m not invisible. I'm wearing a neon yellow safety vest over a neon yellow windbreaker. The trailer’s rain cover is also yellow, so I should pop like a firecracker when headlights hit me, temporal relief that illuminates my path.

Out of the darkness, salvation glows ahead in the form of a gas station. I pull over to search for another outdoor outlet. A woman exits the convenience store, looks at the bike and with a burst of enthusiasm says, “Nice ride!”

Pain in the ass is more like it, I mutter to myself. I spend 30 minutes shivering outside while the battery partially recharges before my final 10 miles to Williams, which begins with a series of wrong turns when Google Maps points me to side roads that don’t exist.

Baby it's dark outside. First signs of light by the interstate near Williams, AZ.

Powering me forward is the distant dream of a gigantic plate of nachos and draft beer. Entering Williams, the battery box turns into a zombie. It’s been totally dead but suddenly awakens to squawk and shudder with anger. Guys smoking outside a bar stare at me like a freak show on wheels.

I stagger into the parking lot of the Highlander Motel, which for $40 is immaculately clean and comfortable. It’s now after nine and every restaurant is closing for the night. I make it to Pancho’s in time for those nachos and a Piehole Porter that’s big on cherry and vanilla. With every bite and sip, I exhale with gratitude.